Go Concurrency Overview

Go’s built-in concurrency primitives are arguably its most famous feature. They provide a simple yet powerful way to build fast, scalable software that can take full advantage of modern multi-core processors. In this post, we’ll explore the core concepts of Go’s concurrency model, including goroutines, channels, and the Go scheduler, and how they enable developers to write efficient concurrent programs.

🧩 The Fundamentals: Concurrency vs. Parallelism

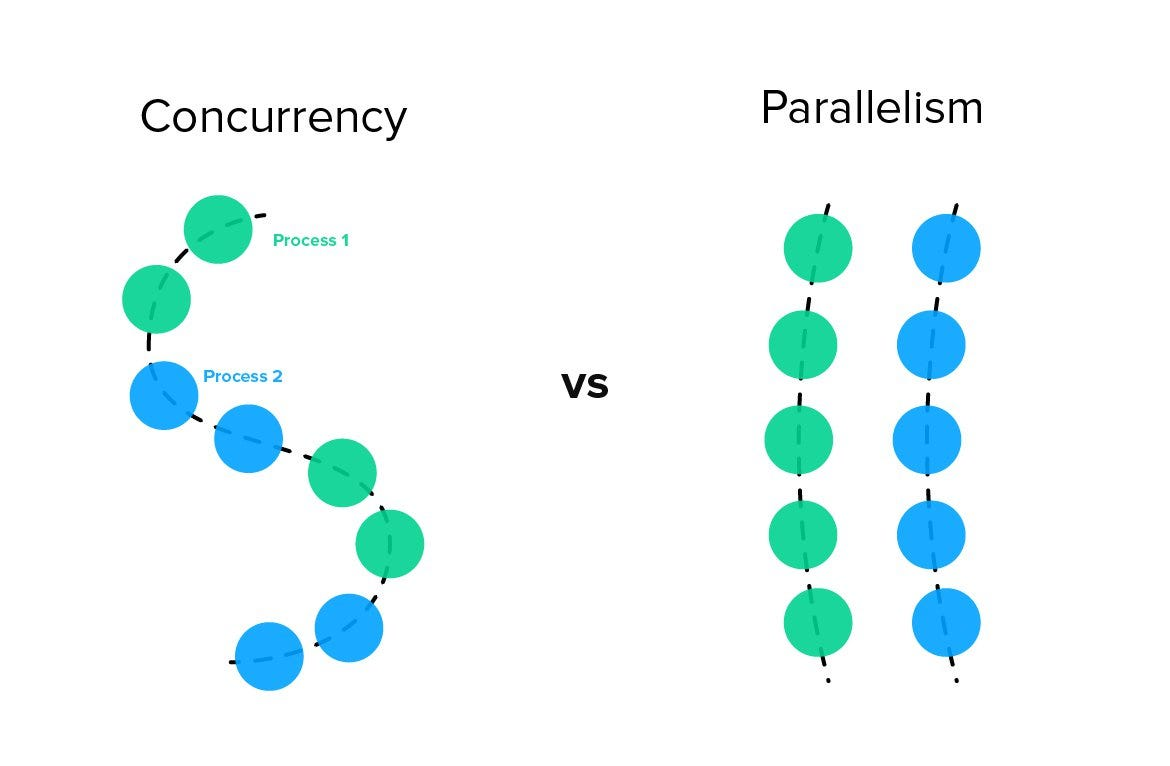

Before diving into Go’s specifics, it’s crucial to understand the difference between concurrency and parallelism: Go’s co-creator, Rob Pike, summarized it best:

“Concurrency is about dealing with lots of things at once, while parallelism is about doing lots of things at once.”

- Concurrency is a design principle: it structures your program to handle multiple tasks that are in progress at the same time. These tasks don’t need to run simultaneously—on a single CPU core, concurrency is achieved through context switching, where the CPU quickly moves between tasks, using idle time (like waiting for a network response) to work on something else.

- Parallelism is the ability to perform multiple independent tasks at the exact same time. Unlike concurrency, where one CPU core switches between tasks, parallelism requires multiple CPU cores to run tasks truly simultaneously. Each core handles a separate task independently.

In real systems, concurrency can still happen within each core, but parallelism scales performance by spreading tasks across multiple cores. Note that a single task isn’t split across multiple cores—each core works independently on separate tasks.

Go’s model allows you to write concurrent code, and the Go runtime takes care of executing it in parallel when possible. This means you can focus on structuring your code for concurrency, while the Go scheduler optimizes execution across available CPU cores.

🚀 The Heart of Go Concurrency: Goroutines and Channels

Go’s concurrency model revolves around two core components: goroutines and channels.

Goroutines: Lightweight Threads

A goroutine is a lightweight thread managed by the Go runtime. Creating one is incredibly cheap and simple—just add the go keyword before a function call:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func sayHello() {

fmt.Println("Hello from the goroutine!")

}

func main() {

go sayHello() // Start a new goroutine

fmt.Println("Hello from main!")

time.Sleep(1 * time.Second) // Wait for the goroutine to finish

}

Why are goroutines so cheap?

- Tiny stacks: Goroutines start with a small stack (around 2KB) that can grow and shrink as needed. OS threads have a large, fixed stack (typically 1-2MB), making them much more resource-intensive.

- Runtime scheduling: Goroutines are scheduled by the Go runtime, not the OS. The runtime multiplexes M goroutines onto N OS threads, leading to much faster context switching.

This efficiency means you can easily have hundreds of thousands of goroutines running in a single application.

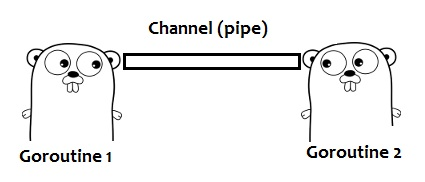

Channels: Communicating Safely

While you can use traditional locks (sync.Mutex) to share memory in Go, the language’s philosophy is best expressed by this slogan:

“Do not communicate by sharing memory; instead, share memory by communicating.”

This is where channels come in. A channel is a typed conduit through which you can send and receive values between goroutines, ensuring safe communication without explicit locks.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

func main() {

// Create a channel that transports strings

messages := make(chan string)

go func() {

// Send a message into the channel

messages <- "Ping"

}()

// Receive the message from the channel

msg := <-messages

fmt.Println(msg) // Output: Ping

}

By default, sends and receives on a channel are blocking. This means a sender will wait until a receiver is ready, and vice-versa. This blocking nature is a powerful synchronization tool. You can also create buffered channels that allow a limited number of values to be sent without a corresponding receiver.

🛠️ Essential Synchronization Tools

While channels are preferred, sometimes you need other synchronization primitives. Go’s sync package provides these.

sync.WaitGroup

A sync.WaitGroup is used to wait for a collection of goroutines to finish executing. The main goroutine calls Add() to set the number of goroutines to wait for, and each goroutine calls Done() when it finishes. Wait() blocks until the counter is zero.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

func worker(id int, wg *sync.WaitGroup) {

defer wg.Done() // Decrement the counter when the function returns

fmt.Printf("Worker %d starting\n", id)

time.Sleep(time.Second)

fmt.Printf("Worker %d done\n", id)

}

func main() {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

for i := 1; i <= 3; i++ {

wg.Add(1) // Increment the counter

go worker(i, &wg)

}

wg.Wait() // Block until the counter is 0

fmt.Println("All workers finished.")

}

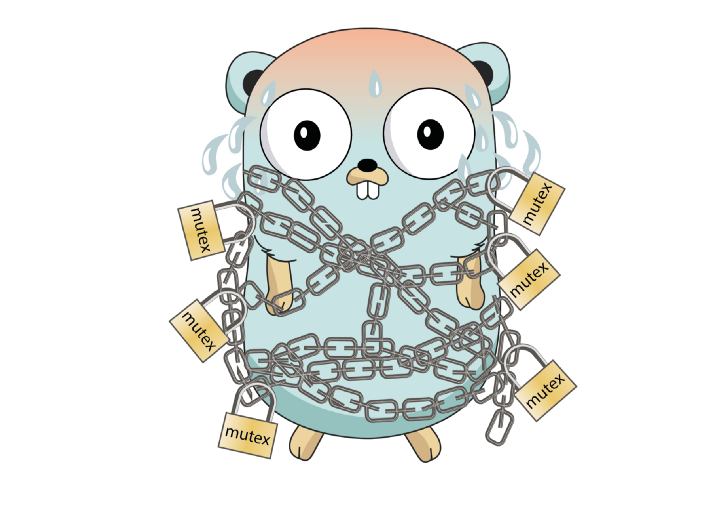

sync.Mutex and sync/atomic

For cases where you must share memory, a sync.Mutex provides a traditional lock to protect a critical section. For simple numeric types, the sync/atomic package offers lock-free atomic functions (like atomic.AddUint64), which are much more performant.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

import (

"fmt"

"sync"

"sync/atomic"

)

func main() {

var ops uint64

var wg sync.WaitGroup

for i := 0; i < 50; i++ {

wg.Add(1)

go func() {

for c := 0; c < 1000; c++ {

// Atomically increment the counter

atomic.AddUint64(&ops, 1)

}

wg.Done()

}()

}

wg.Wait()

fmt.Println("Operations:", ops) // Output: Operations: 50000

}

🏗️ Advanced Concurrency Patterns

With these building blocks, we can construct powerful concurrency patterns.

The Producer-Consumer Pattern (Fan-Out & Fan-In)

This pattern involves multiple goroutines producing data and one or more goroutines consuming it. Channels are perfect for this, allowing you to decouple producers and consumers.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

// Producer generates jobs and sends them to the channel

func producer(jobs chan<- int, count int) {

for i := 1; i <= count; i++ {

jobs <- i

}

close(jobs) // Close the channel to signal completion

}

// Consumer receives jobs from the channel and processes them

func consumer(id int, jobs <-chan int, results chan<- string) {

for j := range jobs {

fmt.Printf("Consumer %d started job %d\n", id, j)

time.Sleep(time.Second)

results <- fmt.Sprintf("Consumer %d finished job %d", id, j)

}

}

func main() {

jobs := make(chan int, 5)

results := make(chan string, 5)

// Start consumers

for w := 1; w <= 2; w++ {

go consumer(w, jobs, results)

}

// Start producer

go producer(jobs, 5)

// Collect results

for a := 1; a <= 5; a++ {

fmt.Println(<-results)

}

}

The Worker Pool Pattern

A worker pool is a common pattern where a fixed number of goroutines (workers) process jobs from a shared channel. This limits resource usage and allows for controlled concurrency.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

func worker(id int, jobs <-chan int, results chan<- string) {

for j := range jobs {

fmt.Printf("Worker %d started job %d\n", id, j)

time.Sleep(time.Second)

results <- fmt.Sprintf("Worker %d finished job %d", id, j)

}

}

func main() {

jobs := make(chan int, 5)

results := make(chan string, 5)

// Start a fixed number of workers

for w := 1; w <= 3; w++ {

go worker(w, jobs, results)

}

// Send jobs to the channel

for j := 1; j <= 5; j++ {

jobs <- j

}

close(jobs) // Close the channel to signal no more jobs

// Collect results

for a := 1; a <= 5; a++ {

fmt.Println(<-results)

}

}

The Publisher-Subscriber Pattern

In this pattern, multiple subscribers receive messages from a publisher. Channels can be used to implement this, allowing subscribers to listen for updates without being tightly coupled to the publisher.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

type Publisher struct {

subscribers []chan string

}

func (p *Publisher) Subscribe() chan string {

ch := make(chan string)

p.subscribers = append(p.subscribers, ch)

return ch

}

func (p *Publisher) Publish(message string) {

for _, sub := range p.subscribers {

sub <- message

}

}

func (p *Publisher) Close() {

for _, sub := range p.subscribers {

close(sub)

}

}

func main() {

pub := &Publisher{}

// Subscriber 1

sub1 := pub.Subscribe()

go func() {

for msg := range sub1 {

fmt.Println("Subscriber 1 received:", msg)

}

}()

// Subscriber 2

sub2 := pub.Subscribe()

go func() {

for msg := range sub2 {

fmt.Println("Subscriber 2 received:", msg)

}

}()

// Publish messages

pub.Publish("Hello, Subscribers!")

pub.Publish("Another message!")

// Close all subscribers cleanly

pub.Close()

}

💧 Preventing Goroutine Leaks with context

A “leaked” goroutine is one that remains active when it’s no longer needed, consuming resources indefinitely. This often happens when a goroutine is blocked on a channel that will never be written to or read from again.

The context package is the standard Go solution for managing the lifecycle of a goroutine. It allows you to pass cancellation signals, timeouts, and deadlines across API boundaries to goroutines.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

// A worker that can be cancelled via a context

func worker(ctx context.Context, id int) {

for {

select {

case <-ctx.Done(): // Check if cancellation has been requested

fmt.Printf("Worker %d: stopping\n", id)

return

default:

fmt.Printf("Worker %d: doing work\n", id)

time.Sleep(500 * time.Millisecond)

}

}

}

func main() {

// Create a context that can be cancelled

ctx, cancel := context.WithCancel(context.Background())

go worker(ctx, 1)

// Let the worker run for 2 seconds

time.Sleep(2 * time.Second)

// Cancel the context, signaling the worker to stop

cancel()

// Give the worker time to clean up

time.Sleep(500 * time.Millisecond)

fmt.Println("Main: finished")

}

By checking ctx.Done(), the worker can gracefully exit when the main function calls cancel(), preventing a leak.

🚦 Common Pitfalls & Best Practices

- Goroutine leaks: Always ensure goroutines can exit (use context cancellation where appropriate).

- Deadlocks: Channels (especially unbuffered ones) can easily cause deadlocks. Make sure every send has a matching receive.

- Race conditions: Use proper synchronization (channels, mutexes, atomic operations) to guard shared data.

- Overusing goroutines: More is not always better. Use worker pools to control concurrency and avoid overwhelming the system.

- Testing concurrency: Use Go’s

-raceflag to catch data races in your code.

📚 Further Resources

- Go Blog: Concurrency is not Parallelism

- Effective Go: Concurrency

- Go by Example: Goroutines

- Go Wiki: Goroutine Leaks

🎯 Conclusion

Concurrency is a vast subject, but Go provides a remarkably simple and elegant toolset to tackle it. By understanding and mastering goroutines, channels, and patterns like worker pools, producer-consumer, and graceful shutdown with context, you can write highly efficient, scalable, and responsive software. The key is to embrace Go’s philosophy: structure your code to communicate safely, and let the runtime handle the parallel execution.

🏁 Final Thoughts

Concurrency in Go is not just a feature; it’s a fundamental part of the language’s design. By leveraging goroutines and channels, you can build applications that are not only fast but also easy to reason about. As you continue to explore Go, remember that concurrency is a powerful tool, but it requires careful design to avoid pitfalls and ensure your programs are robust and maintainable. Happy coding!